What’s in a Name?

If we asked anyone what this coin is, their answers would depend on their knowledge. People who know nothing about old cents would scan the date and would sort out the basics, probably noting the name of the country and the denomination.

Others might know the coin by its “official” name, a combination of an organizational system, and certifications from various groups: “1794 S-67 R3 Head of 1795 PCGS graded MS64 Red & Brown, CAC Approved.”

And yet others would recognize it instantly as the “Crying Lady,” because of the “tears” that drop from her eye to her cheek.

It would seem simple at this point to say that this is a nickname and leave it at that, but, instead, let’s ask some questions about objects and identity, about how ascribing personhood to the inanimate might reshape our relationship with the object.

Let’s back into this project by first considering people. What happens when people’s names are removed or changed by others? What happens to the way they see themselves and how they are treated? It’s easy to think of many appalling examples from recent history where this has happened, but let’s look to science fiction, specifically Star Trek: The Next Generation, to explore this question.

Some speculate that in the original Star Trek, James T. Kirk was modeled on Captain James Cook, and the entire premise of the Star Trek franchise is that the Federation–a group of like-minded, investigative, generally peaceful beings–will explore the Universe. In Star Trek an indomitable captain always helms the flagship. Star Trek: The Next Generation’s, Captain is Jean-Luc Picard. Unsurprisingly, Federation captains are resolute individuals: clearly aware of who they are at the same time as they juggle the demands of scientific exploration and the needs of a diverse crew and as yet unencountered beings and organisms.

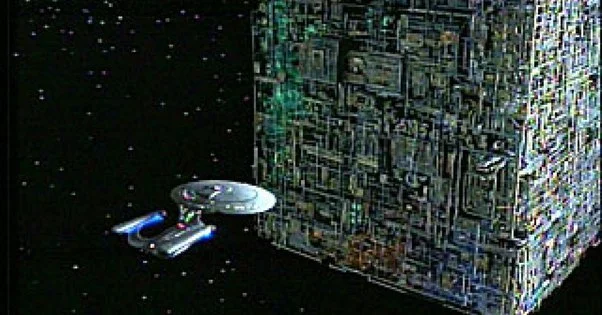

The Enterprise approaches the Borg cube

In one episode, the star ship Enterprise encounters a terrifying threat to humanity: the Borg. They are a collective. They “collect” individual beings, hook them up to their ship, run off of their power and energy, and deny them any individuality. Any Trekie knows the phrase “Resistance is futile.” The phrase comes from this episode: individuals, Federations, nothing can resist the power of the Borg to assimilate and rename beings. When assimilated, an individual becomes one of many–so that their names are no longer Zulu or Sinead or Sisi but “one of 6, or two of 6.” Captain Picard is renamed “Locutus”–suggesting his role as spokesperson of the Borg, and his human knowledge is turned against the ship he captained. The Borg is one of the most terrifying opponents the Federation has known because of their alienness, their square ships, and their forcibly renaming individuals as numbers within a collective group. In this act of domination beings are transformed into parts whose key function is connecting with other parts. Like numbers, members of the borg are impersonal, composed of 10 digits that can be combined infinitely.

For humans, becoming a number dehumanizes. In like way, when looking at certain large cents, we see that the Mint records the number and type of coins struck in a particular year, and we can categorize the differences within those coins. For the collector, these differences mark the coins as individual, and it could be argued that the nickname further imbues the coin with personality. Rather than seeing a coin as, say, 168 of 2,568, a nickname, it could be argued, calls out a coin as noteworthy. How do these nicknames change the way the viewer interacts with the coin?

In certain quarters, anthropomorphism is seen as a weakness. For numismatists,, anthropomorphism can draw someone to the object. While the legitimate name of the coin–1794-s-67-r3-head-of-1795-pcgs-graded-ms64-red-brown-cac-approved--tells us what it is, it does not tell us how someone feels about the coin, nor does the name tell us how or why this particular coin is notable (someone would need to know that S-67 is a Sheldon number that catalogs this particular coin). In some ways, the “official” name of the coin is akin to AKC names of champions. For instance, MBIS MBISS GCHP2 CH Sabe’s Simply Invincible is actually a Boston Terrier nicknamed “Vinny.”

The S-67 is the “Crying Lady.” The nickname suggests depth of knowledge and intimacy borne of effort, and, for those lucky enough to have owned the coin, knowledge and intimacy borne from ownership.

If we look at the nicknames themselves, we first encounter Dr. Edward Maris, author of The Cents of 1794 who nicknamed some 1794 cents based on Roman connections and in Latin, reinforcing Liberty’s connection to the Roman goddess Libertas (He also nicknames them based on Liberty’s appearance.). Within a contemporary American context, this is a decidedly educated, aristocratic space. Thus the “Crying Lady” for Maris is the “Roman Plicae,” or Roman stare. There is, according to Sheldon, “no expression.” Yet when she receives her more American nickname of “the Crying Lady,” the act of crying, an expression of emotion, perhaps changes the manner in which viewers approach the coin.

Is she the Roman Plicae or is she the Crying Lady? I would hazard that people learning about the coin for the first time and reading the names would come to consider and frame the coin differently based on the nickname. In one, Liberty is stand-offish. In the other, viewers are provoked to ask why she might be crying. The nicknames also raise the issue of accessibility. Which America names the coins: highly educated America or folksy America? True, often it can be both, but in Penny Whimsy Sheldon details sitting down at the dining table, the cloth cleaned off, the lamp trimmed, and a box of coins comes out to be detailed and pursued by the family. This is a folksy, relaxed approach in which Maris’s “Scarred Head” becomes “Apple Cheeks”: “the face has exceptionally rounded, full cheeks–a characteristic by which collectors recognize it easily. My father used to call it the Apple Cheek variety” (92). The coin’s defining characteristic is no longer a scar but now the full cheeks of healthy American girlhood.

As Jean-Luc Picard is himself AND Locutus, when taken by the Borg, so the S-67 is both the Roman Plicae AND the Crying Lady: the nicknaming of the coin removes it from its commonality with other 1794 cents and makes her an individual. What’s in a (nick)name? Everything. The lineage, acceptance, and (nick)naming of objects constructs a shifting, contested vision of the future, built upon expertise, power, and maybe most important of all, accessibility.