Humble Beauty

Our first image in this post is a humble copper tea kettle. Supposedly, when the US Mint needed copper to mint coins–and found itself short–many normal objects, such as scrap from ships and household goods, were melted down, including a tea kettle and tongs owned by George Washington. All of these different kinds of copper and any impurities trapped within them affect the coins being made from that copper.

While there is often discussion about the beauty or attractiveness of Liberty, we want to explore how the copper itself, its luster and color, contributes to a coin’s beauty. How do those aesthetic considerations figure into the valuation of a coin? As there are differing standards of beauty from age to age, are there differing evaluations of what shade of copper is most desirable? And how do we value a natural metal whose appearance will age with time?

Probably the first and best place to begin our exploration is by looking at the grading standards and what they say about copper. The valuation for the finest copper coins uses the phrase “If copper, the coin is bright with full original color and luster.” Mint luster “is the sheen, or reflective qualities, that are produced during the minting process.” Note here that “beauty” is originality–the finest coins will be in the most original state, making the “freshest” of coins the most beautiful.

Of course, the coins are over 200 years old, and most people cannot own the highest quality copper coins, so what is valued in the lesser coins? The grading standards tell us that a copper coin of a slightly lower quality “displays original or lightly toned color (which must be designated),” suggesting as above that originality of the coin is most important. Toning copper means using a technique–often heat–to affect the appearance and color of the coin.

Yet if we turn to one of the most notable books written on Early American large cents, William Sheldon’s Penny Whimsy, revised in 1958, we find at the front of the book pages on how to modify the color of copper. In his chapter “Towards a Science of Cent Values,” Sheldon includes a subsection titled “Value as Related to Care and Treatment,” which includes “home remedies” to recolor cents. Probably the most viscerally awful of these is method 6, which requires wrapping a coin in flannel, attaching with a string belt to the waist and tucking this beneath one’s underclothes. Sheldon notes that winter underclothes are preferable because they hold more sweat. His caution will be met in the 21st century by howls of horror: “The underclothing should of course in no circumstances be removed or changed until a satisfactory color has been achieved” (47).

Where does this leave us with the aesthetics of aging copper? Sheldon himself touts the beauty of aging copper:

“The big cent is something more than old money. Look at a handful of cents dated before 1815, when they contained relatively pure copper. You see shades of green, red, brown, yellow, and even deep ebony; together with belendings of these not matched elsewhere in nature save perhaps in autumn leaves.” Later in the same paragraph he rhapsodizes that “every early cent has a character of its own.”

Economic value, via grading, tells us what copper color is worth the most. Reading the comments of collectors offers us a wider view, one perhaps more in tune with Sheldon’s call to recognize the individuality of large cents for the “intrinsic beauty and variability of old copper.”

Could we explore the connection between the variability in copper and the variability in women’s “beauty”? As we establish standards for grading coins, so there were standards of beauty for women in the 18th century. Like the standards for coins, these were very clear expectations of female beauty, and like the coins that may or may not have been toned or in other ways doctored, so women’s beauty was supposed to be natural.

One of the most known and most idolized women of that time was Lady Emma Hamilton, who sat for famous artists, married a Lord, and was the mistress and then wife of Lord Nelson. Attacked as being no longer beautiful and being “fat,” it turns out that Emma Hamilton was pregnant with Lord Nelson’s daughter, Horatia. Emma Hamilton’s is a sad story, filled with class prejudice, increasing poverty, and alcoholism; it is also a story about the natural shifting and changing of the female body. If we recall the many discussions about female beauty and the appearance of Liberty (see this blog post), then forcing a standard of beauty upon Emma Hamilton that she had contributed to but had outgrown insists upon timelessness and youth.

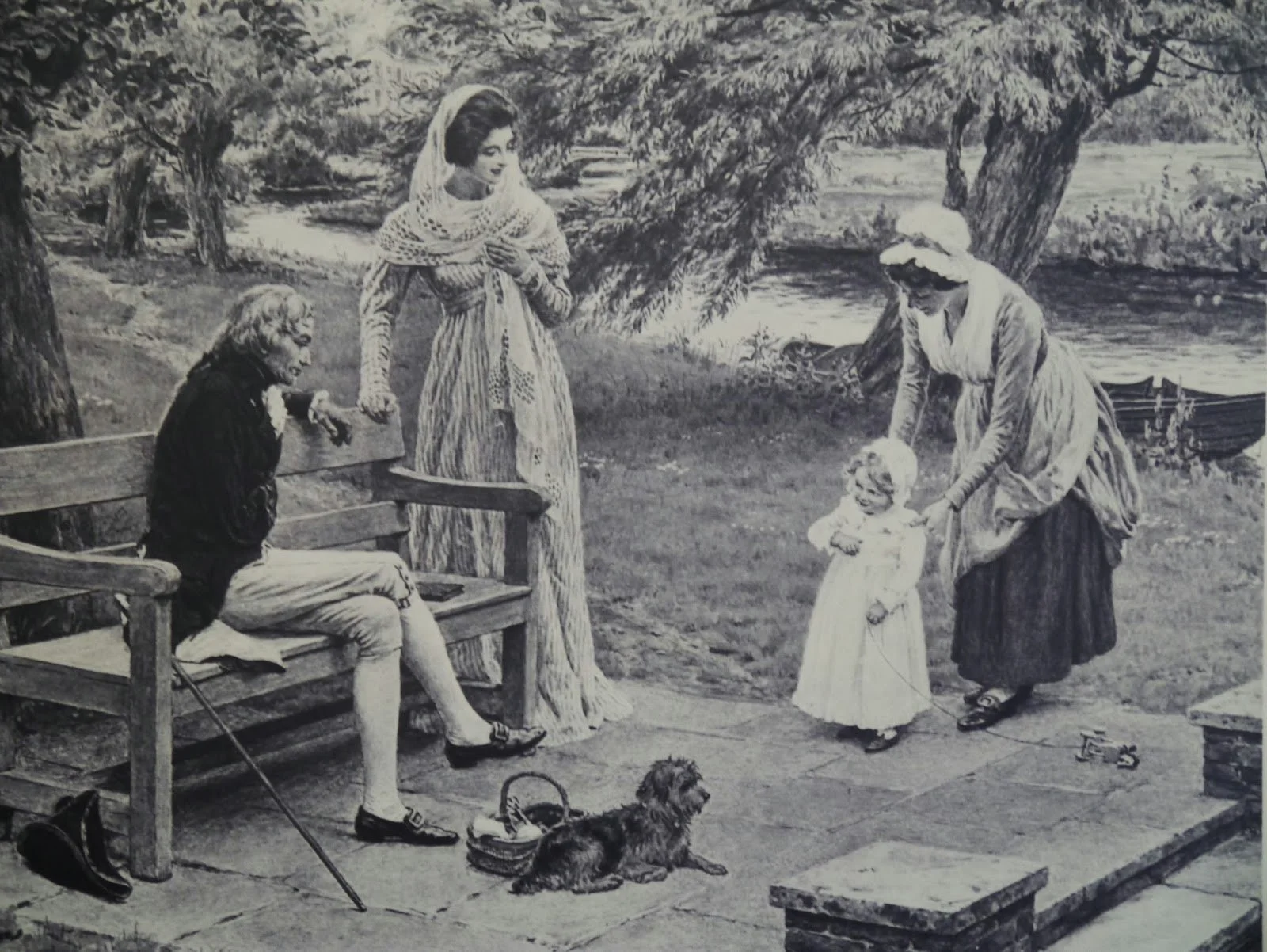

Nelson, Hamilton, and baby Horatia

Like people whose cells age, copper coins, change because of the nature of the metal. While the grading standards tell us what is most desirable–at least in terms of collecting and valuing–reading the comments of collectors about the color and appearance of their copper coins speaks to the place of individual choice about what makes something beautiful.

Philip Kadaev writes of his 1758 2 Kopek that “[a]lthough, the coin no longer possesses its earlier luster and sharp details, it still contains an element of aesthetic beauty that can only be developed with age.” Reading Tom Deck’s description of his 1794 coins reveals a variety of aesthetic valuations based on color. His 1794 S-23 “has a few nicks and di[n]gs but an amazing tan color.” His Venus Marina (see this blog post for more on nicknames and coins) has “good color”--a phrase more similar to the grading standards, where “good” is not quite defined. But his S-42 has a noteworthy comment:

“While the coin may have been burnished, [. . .] I can't tell - it's definitely one of my favorite cents, based on appearance alone.”

And that is what beauty is about: what stirs and entrances us. There are, have been, and always will be groups that sanction what is valuable. Their descriptions of value protect the objects and some within these groups will try to mandate a particular, dominant style. Think here of the mask that makeup artist Max Factor placed on wannabe starlets’ faces, when a studio signed them so that their faces could match the ideal.

Beauty, though, transforms us. We feel it more easily than we can express in words what it is. Epitomized in humble copper more than 200 years old, beauty can be tan, deep brown, almost black. It can shine with aged luster, or its dings and tarnishes can make it more precious to the eye. There is the economic value. And then there is the aesthetic value. There is the value of an Early Cents collection that is the first, but there is also the value in what you want and are able to collect–and that collection, in many ways, will be the most beautiful.

As a counterpoint to Max Factor’s identical beauty, let’s end the discussion of humble beauty by looking at a coin that might, perhaps, have had a smidgen of Washington’s tea kettle: the S-24–a beautiful chocolate brown that shows off her rounded cheeks and wavy hair. Do you find her beautiful?

S-24, Apple Cheeks, R1, AU-58