Language, Coins, Economy

When it comes to the 1787 Fugio cent and the 1793 Chain cent, each coins’ design speaks to competing economic policies.

wild turkeys

Today I saw a bald eagle in the wild. It flew along the boundary between a lake and the land, its wingspan massive, its white head unmistakable. It then sat atop a dead tree, utterly unconcerned about people nearby. On my way to the eagle, I had also passed some wild turkeys, which, though dim-witted, are companionable and not unattractive. These two very different birds set me to thinking about Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and their competing visions for the country.

While the birds encapsulate different visions for the nation, so too do coins. Let’s take a look at the first coins minted under the Articles of Confederation and those minted after the Coinage Act of 1792 was passed by the First US Congress (see this post for more detail about the 1793 chain cent). In this post we will explore how the different iconography on the coins indicates different views of the country, the economy, and how currency works. Do the rejections of and changes to some devices from 1787 Fugio cent to the 1793 Chain Cents suggest different ways the nascent country conceived of capitalism?

Perhaps one of the most alluring points about the Fugio coin is the assertion that it was designed by Ben Franklin. After movies like National Treasure, it’s easy to think about Benjamin Franklin, masons, and money and imagine a world of secret symbols available for decoding by people who belong to secret organizations or by people who find the hidden key. Joshua Glawson has written a clever article that decodes the Fugio cent as a lesson in the values of Benjamin Franklin particularly through Poor Richard’s Almanack and Franklin’s Autobiography. And while some numismatists debate who exactly designed the Fugio cent (see Craig Sholley’s objections to Glawson’s article here and Eric Newman’s careful discussion here), it’s clear that some of the elements on the Fugio borrow elements from Franklin’s Continental dollar.

Yet read any article about the Fugio cent and the debate surrounding a United States currency and you’ll find people decrying the Fugio cent and arguing that it was not popular. “Popular” here should be defined: while the US paid for copper, many of the coins were never delivered, and those that were delivered were “light,” meaning they were not worth their denomination. If someone owed you three cents, then in the 18th century those three Fugio cents should be composed of three cents worth of copper. But if someone hands you three “light” Fugio cents, you could instead be paid two and a half cents or less. Lack of popularity, then, means people realized they were not worth their face value (side note: if you’re interested in how people come to trust currency, take a look at this post on our website and this article on the start of US coinage). Once you know about the fraud in the minting of the Fugio, it’s easy to understand the details in the Coinage Act of 1792, especially about the appointment of the assayer, chief coiner, and treasurer (see sections 4 and 5), as well as a sanctioned weight for each currency. Today most of us see money as representational–a cent equals one cent, not because it is worth one cent (famously, making one penny costs two pennies), but because we all agree that a cent is “worth” a cent (in actual fact, in 2025, the metal in a cent would only bring .75% of a cent). In the 18th century, however, the metal in a coin had to equal the face value of a coin. Without that, a coin would be undesirable and a currency would be unstable.

Turning to the 1793 cents minted under the Coinage Act of 1792, most numismatists agree that the reverse design of the 1793 cent borrows from the Fugio cent, which is easy to see when looking at the coins side-by-side.

1793 Chain cent

1787 Fugio Cent

Numismatists refer to the 1793 cent as the “chain cent,” generally assessing that it was not “well-received” because of the depiction of Liberty on one side and the chains on the other. Whereas in 1787 the chains had been a sign of strength and unity, by 1793 people “rejected” the chains, some suggesting that the chains now were seen as a reference to slavery and being chained together, which would curtail liberty. Proof of this is the quick replacement of the chains with the wreath.

1794 Liberty Cap cent with wreath reverse

While we can certainly acknowledge these approaches, what if we look at the change between the coins through Franklin’s economics and philosophy? I suggest we see the currency changes as changes not only in representation of the young nation but also in approaches to mid to late 18th century economics. Does the “rejection” of the chain cent suggest a change in the view of the mechanisms of the economy of the United States?

In “Pudding Economics," Howard Horowitz argues that “identity and ultimately the character of society are fabricated through ongoing, visible, and expanding social intercourse (to use a common term for commerce in the period)” (598). For Franklin, a printer who understood the persuasive and political power of images, it is not a stretch to think that designs on currency itself could help shape the character of society.

While Ben Franklin is most known for his Autobiography and Poor Richard’s Almanack, Franklin wrote copiously, including about thrift and other forms of economy. A country’s economy and its individuals need at least some material reward, or “pudding.” Given the fraud in the minting of the Fugio cent (and the scanty production of the coin), there’s some irony that in his 1729“Modest Enquiry” Franklin explained that scarce coinage gave advantage to Britain. Horowitz summarizes: “Franklin argued that scarcity of currency staunches even transatlantic trade and increases interest rates, further stifling commerce (“Modest Enquiry” 4). ‘Want [lack] of Money in a Country reduces the Price of that Part of its Produce which is used in Trade,’ Franklin writes. ‘Because, Trade being discouraged by it as above, there is a much less Demand for that Produce’ (5). Scarce currency seems in itself to depress demand. People cannot buy even discounted goods without money to spend” (Horowitz 605).

On the other hand, Horowitz comments, “[w]hen credit is available, people spontaneously incur debt, which incites more trade, inciting more debt, and so forth. Want, trade, debt, trade, want, debt, trade, etc. The dynamic has for Franklin the virtue of democratizing access to capital. As plentiful currency reduces interest rates (“Remarks” 4–5, 22), its inflationary effect reduces the cost of debt, disappointing creditors, whose receipts on loans lose value (“Remarks” 16–17, 18, 22)” (608). Let’s stay with the cycle–the chain–of want, trade, debt– that ”democratizes capital”: what better imagery than a chain for a coin that circulates among the population, especially a low-denomination coin?

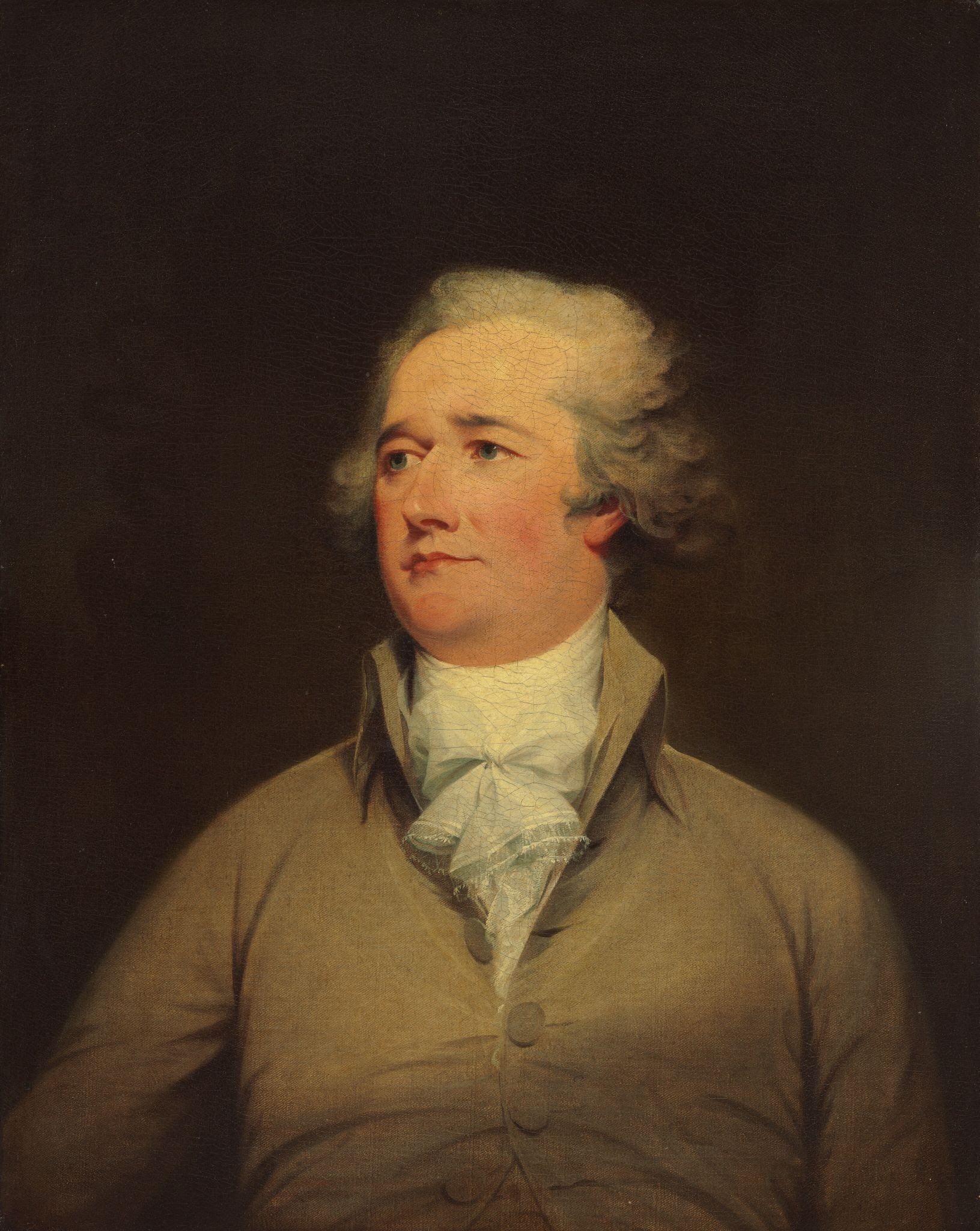

Alexander Hamilton in 1792

Between 1787, the year of the Constitutional Convention, and 1793, discussions about the nation’s economy roughly break into the pro-Adam Smith laissez faire group (it is generally agreed that Franklin probably met Smith in London,) and a group that is more interventionist, headed by Alexander Hamilton. In an interview in the Boston Review, “What We Still Get Wrong about Alexander Hamilton,” Christain Parenti summarizes Hamilton’s economic policies. “The Republic’s survival was not guaranteed by military victory, nor by experiments in democratic government alone. It required a profound economic transformation that took decades to achieve. And that economic transformation did not just occur naturally—it had to be produced by a sophisticated, innovative, and sweeping program of government action.”

Parenti notes that Hamilton’s Report on the Subject of Manufactures “opens with a direct attack on Adam Smith and laissez-faire. Keep in mind, Thomas Jefferson called Wealth of Nations the best book in existence. It was very popular among the Founders.

In his dissent against this orthodoxy, Hamilton argues that free markets only work if your national economy is already wealthy and powerful. In other words, if you are Great Britain. But for a fragmented underdeveloped economy emerging from war and colonial dependence, free trade is a disastrous mirage. The “invisible hand” will not deliver development. Government has to conceive and execute a plan for that to happen.” Stabilizing an economy via a reliable currency would be part of that plan, just as Franklin understood that having currency would fuel an economy, the cycle of trade, want, debt mentioned above.

Pragmatically, did Franklin’s iconography–not only on the Fugio, but on the Continental, on flags and pamphlets and more—convey to people this desire for “democratized” access to capital? We could certainly make a case, especially as the chain circles around “We are one.” On a coin that mediates the exchange of labor for the exchange of labor what makes us one is our ability to participate in that cycle of want, trade, debt, which, with abundant coinage, and undergirded with a recognition of the brevity of time, assures success for all. In this way, we could read the Fugio cent as a symbolic enactment of Franklin’s economic philosophy. Given Franklin’s turn/talent at printing and design—for instance, his dismembered snake—it’s not too much to think that he understood the Colonial mind and the power of symbols to persuade people to action. And it is also worth pointing out that “all” did not really mean all. Clearly, there were exclusions.

If the reverse of the Fugio models inclusive, dependent economies, both monetary and political, the obverse offers lessons about how to achieve those ends. What qualities or elements must be in place for people to enter the cycle of want, debt, trade? To begin to answer this question, let’s flip over the coin. Discussions of the obverse of the coins range from rather snobby attacks on its aesthetics, to arguments that the ray of light suggests a Palladian influence, which then refocuses the discussion on the Roman revival, and concludes that Americans were deeply imbued by Roman values, to links to the moral values extolled in Poor Richard’s Almanack and Franklin’s Autobiography. Indeed, Franklin has been called a “savant of capitalism.”

In the change between the Fugio cent and the Liberty cents was there a struggle over the conception of the relation of people to each other–the chains on the backside of the Fugio and the Liberty coins–as well as a question of what key qualities would hold the country together? One coin is minted during the year when most recognized that the Articles of Confederation could not work and thus they called for a Constitutional Convention. The other coin is minted under the auspices of an act of Congress, and direct mention in the Constitution. Returning to the obverse of the Fugio, the devices show a focus on surveillance, by others and by self–time is flying so make sure you use–and spend–it well. By 1793 these devices are replaced with a word, Liberty, and its conceptual embodiment in the face of Liberty herself (and as Liberty changes across coins in the late 18th century, we see the metamorphosis of a young, more helpless “Liberty” who requires protection). Does a schism grow between views of community and economy in 1787 vs. ideals and national self-presentation in 1794 ? Does the replacement of all devices from the Fugio by the time of the 1793 wreath cent suggest a reorientation away from Franklin’s shared economy to Hamilton’s belief expressed by Parenti that “Economic transformation did not just occur naturally—it had to be produced by a sophisticated, innovative, and sweeping program of government action.” The individual might still need to participate in the debt, want, trade cycle, but will do so as an enactment of Liberty, and with a wreath, which suggests stability and empire. The government’s requirement of some of the devices on the cent, along with clear details for the amount of copper in the coin, signals a new age of nation building.