Changing Liberty

Depictions of Liberty changed rapidly on early cents.

What does the changing picture of Liberty say about the country’s view of itself?

Let’s start with a few things that seem unrelated:

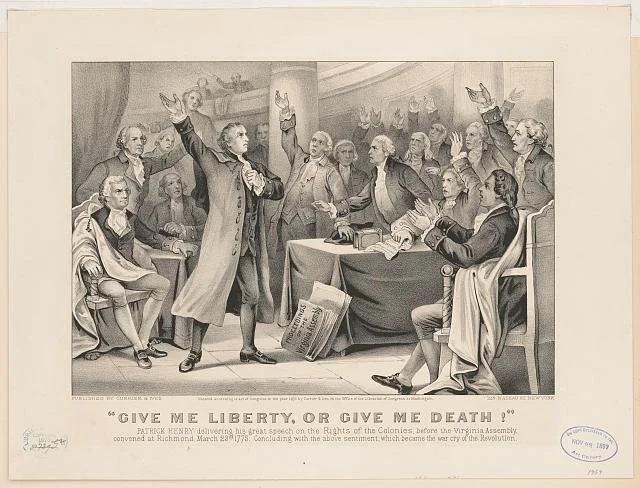

The earliest is “Give me Liberty or give me death!”—Patrick Henry’s famous speech in 1775 to the Virginia Assembly.

Patrick Henry’s speech—as drawn by Currier & Ives in 1876, 100 years after the American Revolution began. Note the raised hands and gestures towards providence.

Next we have “Article I, Section 8, Clause 5” of the Constitution, which gives Congress the power “To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.”

Finally, look at these three images of Liberty, from 1793 (two coins) and 1794:

A 1793 “chain cent.”

1793 Wreath cent

What links these elements is the idea of Liberty as a key principle animating the Colonies’ war against the British and the new Republic born from winning that war. Given the scale of the war and its duration 1776-1783, “Give me liberty or give me death” is not an advertising slogan—it is a contract between the rebellious citizens and the British. It indicates just how serious their desire for liberty was that they would—and they did—die for the ideal that their new republic would put into practice. A demand for liberty and a promise to be willing to die for it, Henry’s call is similar in approach to the Declaration of Independence, which is a demand and a list of grievances against the King, all of which justify the revolution itself.

Our second element comes from the Constitution’s Article 1, about the powers of Congress. Section 8, clause 5 sets up the mint. Part of the problem of the colonies and their confederation was the wide variety of coinages, which were loosely accepted across the colonies. The Articles of Confederation offered a weak central government. In the Constitution, however, the founders gave more power to the central government, including the ability to mint one set of coins that would be used by all, signaling just how powerfully important coinage will be to the new country. For people used to colonial tokens or British currency, what would it mean to have their own currency, and what ideas or ideals should that currency inscribe?

And that brings us to the images of the 1793 cent, the first cent minted by the US Mint, and in some ways the most important coin minted that year. After all, most people would have access to a cent, versus a dollar. While “only” worth 1/100 of a dollar, its very ubiquity makes it centrally important.

If we keep in mind the three points above, what do we make of the depiction of Liberty herself on this first cent? What do you notice about her face? What emotion do you see on the face, and why?

Since the Greeks and the Romans, virtues and ideals have been personified, especially as gods or goddesses. For these civilization what was most important was the very general nature of the representation. Liberty for the Romans was not an individual but a concept—so there are items that she often appears with that indicate who she is. David Hackett Fischer in Liberty and Freedom, A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas makes the interesting point that in US coins, Liberty becomes more personalized as we move into the 19th century. She exists more as an individual and less a representation of a concept. What then does that say about changes in the concept of Liberty?

We could argue that that act of individualization and the frequent changes to the coin in its first two years addresses anxieties about nationhood and national value experienced in other realms, such as literature. For instance, in literature, the colonists had broken with a country that had an acknowledged, respected literary tradition. In the 1770s the United States did not have a similar heritage. Behind these concerns was an anxiety about the status of the new nation. Indebted to France, their economy tattered, their shared literary heritage rejected, on what basis does the country claim ascendence?

I would suggest that part of how they do this is to mint their own, national coinage. The coin will have nothing to do with kings or queen, but, in the case of 1793, will have everything to do with the animating principles that won the war, such as an unswerving belief in the principle and right of Liberty. Putting Liberty on the coin shares with the populace—both those who can read and those who can’t—a fundamentally American principle. This sounds as if the coin should be received with applause, but no.

Many numismatic websites detail how people dismissed the 1793 chain cent as not being popular, and thus requiring a different design. But let’s slow down and consider exactly what doesn’t work on that first minted US cent, and then let’s dive into what that iconography says about the country at the time.

Many people discuss how the newly liberated country rejected the chains on the obverse of the coin, saying that the chains, rather than suggesting the strong connections of the new country, instead suggested the chains of empire and slavery from which the new country broke free. The second iteration of the coin replaces chains with the wreath. This change from chains of connection—not chains of bondage—to a wreath with laurel, from a forging of an unbroken chain, to ancient symbols of victory and peace, suggests a changing iconography and shows us the importance of the image on the cent, arguably one of the denominations handled the most by people in the young country.

Turning to the obverse of the coin, we find a Liberty of indefinite age—not old—a woman with wild, free hair. According to Wikipedia, newspapers of the time commented that Liberty appears to be “in a fright,” but if we look closely at the coins, is she in a fright? Make a frightened face yourself. What happens to your face? Liberty on the first 1793 cent looks clear eyed into the future. Her uncoiffed hair streams behind her. Note the set of her chin and her mouth. Rather than fear, I would argue we see the resolve of Liberty and her refusal to tame her wildness. If this can be an interpretation of the coin, though, where does that leave the newly formed country? How is Liberty domesticated for a new, free country that needs to build a coherent identity? We see that attempt to build coherence in the structure of the Constitution itself, but wild Liberty is unpredictable—and powerful.

Fischer has commented that 1794 large cents, which depict Liberty with the liberty cap behind her, wears her hair in a “free” style typical of women in the 1790s. If we look closely at the images, however, we see that the hairstyles have a certain amount of artifice to them. The “freedom” of that hair differs dramatically from the first coin. It is an artificial freedom.

For instance, here is a 1797 portrait of Anne Willing Bingham, herself a model for US coins. Note her hairstyle.

In a society constructed after a long, traumatic war on its own ground, and a country that still enslaves people, must Patrick Henry’s do-or-die liberty give way to a more domesticated liberty? Does the ambiguity of the first cent—are those chains of bondage or of connection, or, more interestingly, of both at once—need to be replaced with a young, coiffed, domesticated Liberty whose attraction lies in her recognizable beauty, not in the unpredictable power of her wildness?