Teaching and Learning Resource

How Far Should a Revolution Go?

The argument for natural rights—including liberty— enshrined in the Declaration of Independence collides with the desire to deny those rights to various people.

How do we understand the promise of rights-based change with the fact of constricted rights placed on many people? When is a revolution over?

Analysis, Insights, Links

-

Analysis

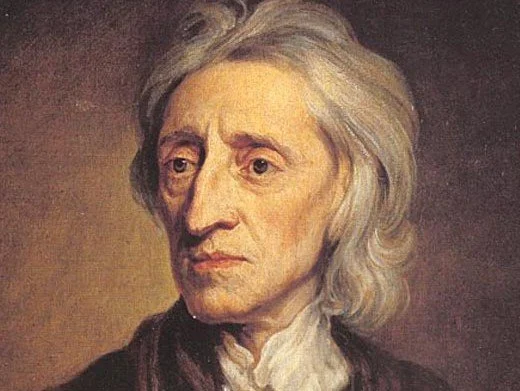

Natural Rights philosophy was increasingly popular in the 18th century America, where it owed much to the philosophy of John Locke.

Natural Rights philosophy means that there are certain rights that inhere in people. The rights are not given or granted, nor can they be taken away because they are universal to all people.

When people discuss Locke (1632-1704) he is often contrasted with Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679). Hobbes believed that people are very similar, and thus that they need a strong ruler. In contrast, Locke believed that in a state of nature, people are very similar but ”there cannot be any subordination among us,” he says—and thus they need an equitable government. In his own way, Hobbes sees what we might consider the equality of everyone, but rather than celebrating it, he sees it as leading to war. He tells us in Leviathan that the state of nature is a state of war; thus, he tells us, people (in this case the English people,) need a strong monarch.

In contrast, Locke emphasized a social contract in which natural rights are supported by the law of nature. The law of nature enables people to create governments .

Locke’s work became particularly important from the mid-18th century on when his ideas about the separation of church and state and about the social contract influenced American patriots.

While Locke is undoubtedly influential on the idea of the social contract, and while it is easy to see his idea of the right to “the life, the liberty, health, limbs or goods,” in the Declaration of Independence’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” there were additional influences on the discussion of revolt and self-determination.

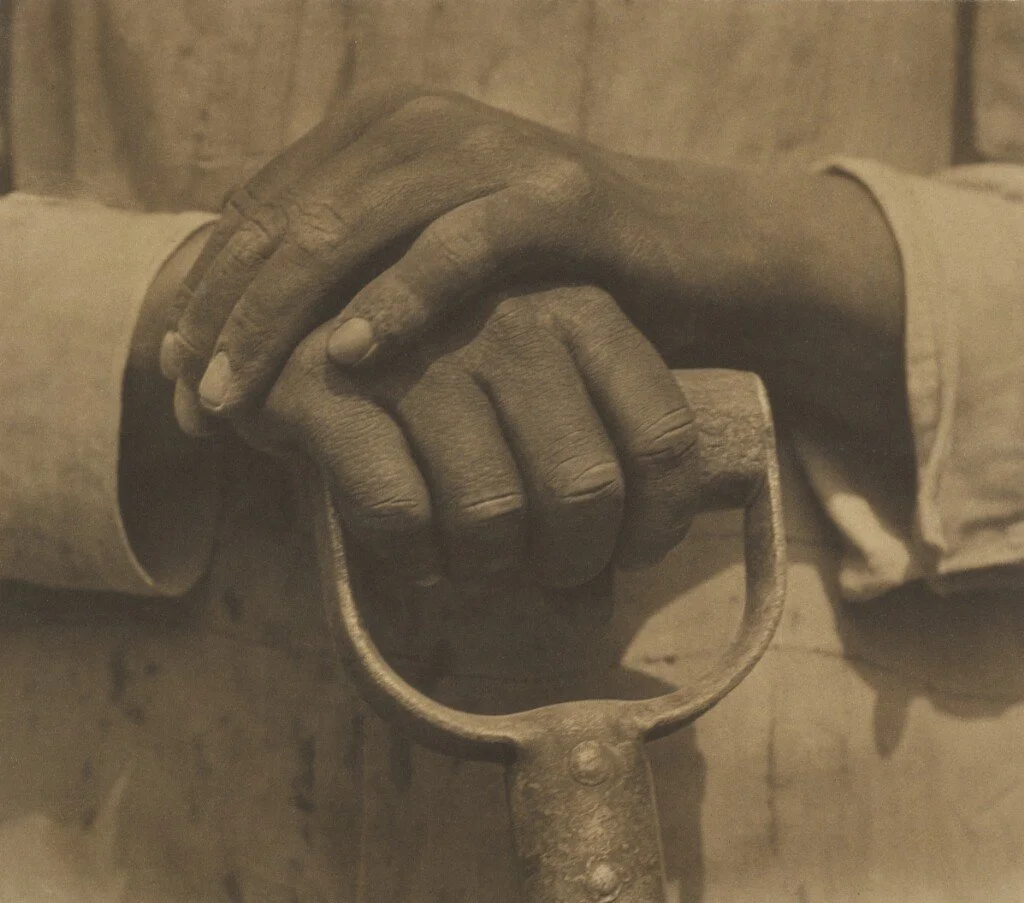

Rather than focusing on those voices, we want to raise the question of how and when the those rights adhered to some and not to others, such as women and slaves. You might like to take a look at this article, which contrasts “daughters of liberty” with “women of the revolution,” and provides and important overview of the degree of change experienced by diverse women, including enslaved and Native women, during and after the Revolution.

Key here is slavery and how that persists, given Natural Rights philosophy. The scope of this issue is enormous. What we want to stress is that unequal treatment of people persisted at a moment of revolution based on perceived understandings of “universal” rights.

-

Insights

Here are three different views on revolution and power.

Introduction to Expand or Die: The Revolution’s New Empire

Discussion of the way we understand revolution and the different speeds of revolution.

“Washington on Your Side,” from Hamilton. Where do we see power colliding among the men with power?

And here is a 1904 article on the Constitution and the compromises made during the Constitutional Convention.

-

Links

Here are a few links that offer further insights into revolution in general and the American Revolution.

Revolutions end when political certainty is reduced.

Locke, Tolerance, and a Recently Found Document

Quick overview of changing views on women in the American Revolution.

Questions

Questions help us cultivate curiosity. Use these questions to begin your own journey thinking about the topics. If you’re a teacher, these questions offer you some starting points for class discussion. All questions are designed to encourage people to make links between the topics and their own beliefs.

When is a revolution over?

Activities

Our suggested activities use cultural artifacts to engage students in thinking through abstract ideas. Each learning resource includes a specific focus and objectives. We encourage you to choose relevant materials for your class from the Insights and Links sections above. Please use the Analysis section and links as background knowledge for your lesson.

K-6

Note: Some would argue that young children are not capable of philosophical reasoning. There are some excellent resources for teaching philosophy to children, as well as discussions of why we would want to do this.

Goal: explore the idea of natural rights

Outcomes: Younger students will create a drawing that shows them how they as individuals are surrounded by structures that ensure their rights as well as the rights of others. Older students will write a sequel for a scene from a movie, and will be able to enumerate the changes in certain “natural rights.” They will also be able to summarize and explain natural rights philosophy.

Activities: Younger children—discussion and drawing; older children—write a script and act it out

Time: Younger children 30-40 minutes; older children approximately two class sessions.

Younger children: Begin with very concrete choices we make, such as crossing the street, and from there segue to a conversation about “rights” that we have. The idea here is to encourage the children to consider how their actions as individuals can sometimes collide with their actions as members of a community, such as a family, a school, a town, and so on. One example that might begin this lesson would be riding a bicycle. Ask them where should they ride a bicycle? On a path at a park? Or in the road? Let them have fun with this. Most will know that they should not ride in the road. And most will know it’s a matter of safety, which prioritizes them. Are there other people who might be upset if they fall off their bike and are hurt? At this point, depending on grade, you might introduce the idea of government. Who or what makes sure everyone is safe or everyone can ride their bike? For an activity, have children draw in the center of the paper, one of their favorite activities they do outside. Then have them draw a circle around the activity. In this bubble, who wants to keep the children safe? (Answers might be an older sibling, or a grandparent and so on.) Then have them draw another circle, and ask the same question. By the end of the lesson, they should have a physical representation of how they are surrounded by different

Older children: Show them the Will Smith movie The Pursuit of Happyness. Then break them into teams and ask them to write a sequel, taking the principles of The Declaration of Independence into account. It’s also possible to choose one or two scenes to focus on, after they have seen the movie. The students could write sequel scenes. Part of the goal here is to have students enquire into the key rights expressed in the Declaration of Independence. For very interested students, it might also be interesting to tell them that whereas the Declaration lists “happiness,” Locke wrote “property.” Given the movie, what do students make of the difference between “happyness” and “property”? Students might like acting out a scene from their sequel. Discussion after each scene could explore the ideas that they believe have shifted or remained the same.

7-12 and Beyond

Goal: Exploring the relevance of rights

Outcomes: Students will be able to enumerate key rights expressed in three major documents. Based on their analysis of what they consider key rights, they will write a Declaration of Rights for the 21st Century.

Activities: Comparison/contrast, analysis, projection, writing

Time: At least several nights of homework, one class session to prep and discuss, and one class session to present—and debate—their new Declaration of Rights for the 21st Century.

The Declaration of Independence birthed many other documents based upon it, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions in the 19th century, and the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, written after WW2. Begin by having students compare and contrast the key statements of rights in these documents. They might do this as a chart, with different teams as specialists on certain documents, or they might focus on a right or group of rights, and then trace across the documents the changes and evolution in that right. Once students have a solid understanding of the rights, ask them to generate a list of 20 key rights they think all humans should have. This could be done individually first, with fairly large group debriefing, which would then be presented to the class. Part of the goal is for students to try to reach a consensus about what the key rights are for now. For instance, should there be a right to digital privacy? Finally, rank the rights, asking them to discuss and assent to what is most important. Students will now be in a position to create—individually or in fairly small teams of no more than four—their own “Declaration of Rights for the 21st Century.”

How should we deal with ideas and ideals that animated the Revolution but that have not yet come to pass?

If you were friends with Lin Manuel Miranda, who wrote Hamilton, who would you ask him to write a musical about, and why?