Teaching and Learning Resource

The Paradox of Revolution

Even though the American Revolution ruptured the relationship with Britain, the country still needed essential materials from the UK.

How much of the old country should be discarded after a revolution?

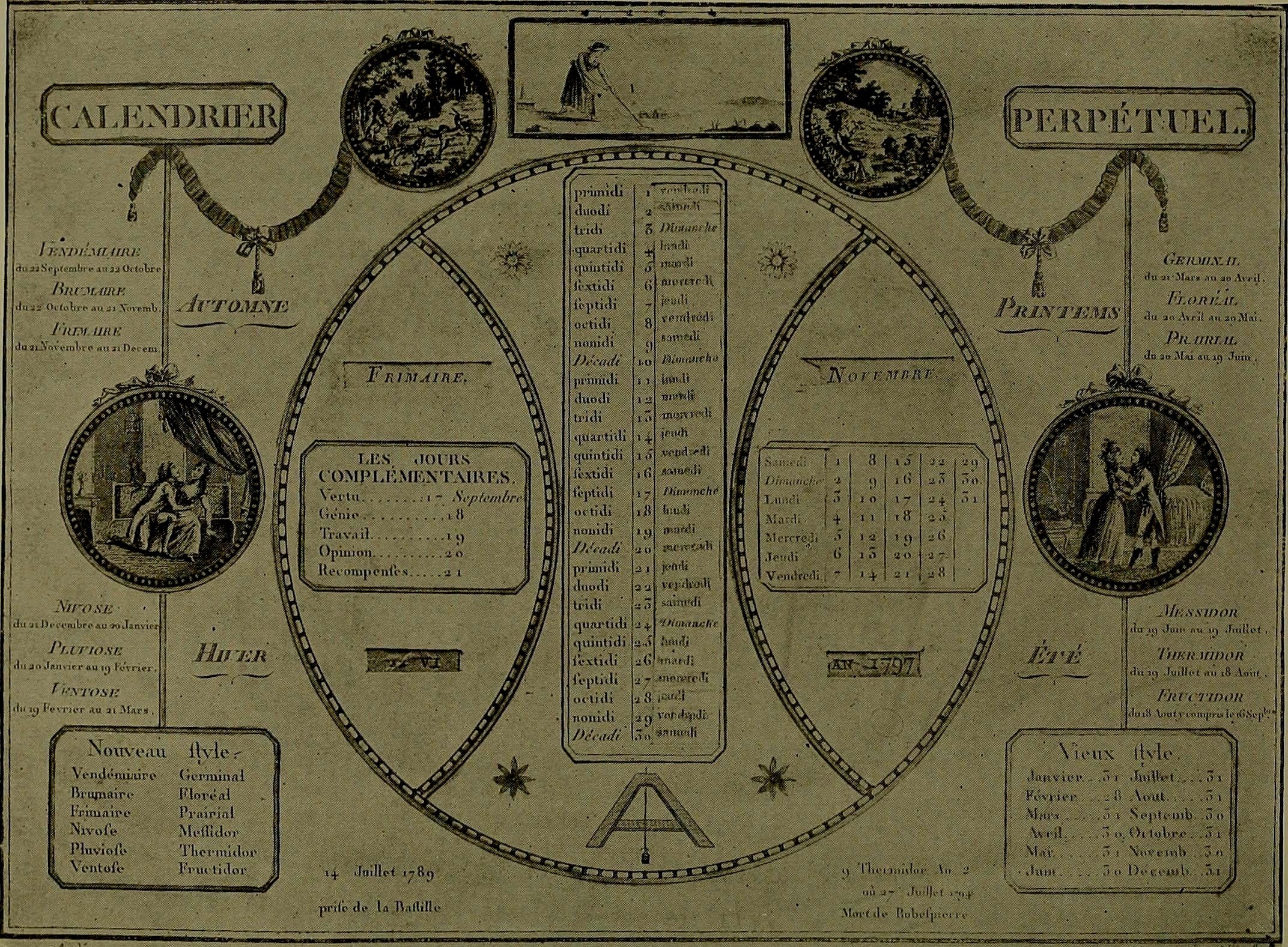

The image behind this text is of the French Revolutionary calendar. Desiring to rid themselves of as much of the old world against which they revolted, the revolutionaries changed even time itself. The year of the revolution became Year One. Months and seasons got new names. In constrast, the new America had a different reaction to its revolution than did the French, perhaps, in part, because of its geography and separation from Europe.

Analysis, Insights, Links

-

Analysis

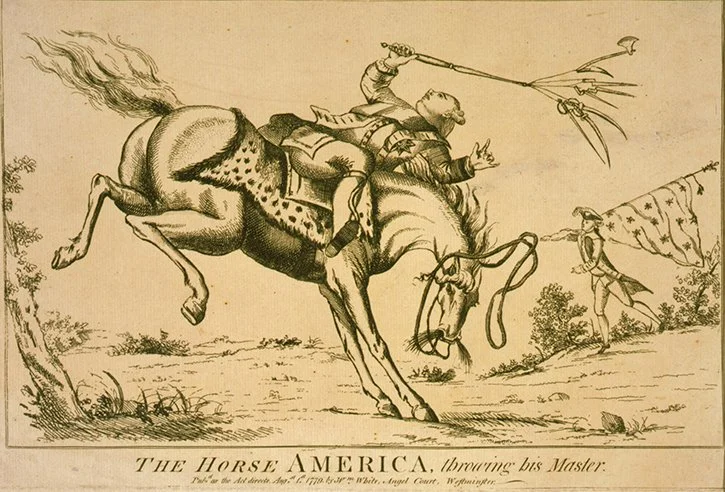

While most contemporary people think of revolution as chaotic and designed to overthrow the old and replace with new ideas, that is a relatively recent idea.

The Glorious Revolution in England in 1688 was not this kind of revolution—it was designed as most revolutions were—to return to an earlier, better idea. Think of how the earth revolves, bringing us back to the same astronomical position in a year. After the American and French revolutions, however, the meaning changed.

The new, the different was desired, and it was won at great cost. Once the battles stopped, it was time to think about what the “new” country needed and how to get it. As we can see with the calendar at the opening of this page, the French Revolution wanted to do away with everything and start anew, redesigning time for everyone. They also redefined geography, changing the traditional names of French provinces.

In the case of the United States, although the changes were not as dire as after the French Revolution, many of the founding fathers came to have significant questions about the possibility of the American project they began. People fought against rich absentee landlords for the right to settle land. Alcohol consumption was astronomical. Most importantly, the Articles of Confederation were not strong enough to hold the country together. Eventually, in 1787, the Constitutional Convention would gather to create a constitution written to ensure certain rights.

While US Republican self-government was formed in the wake of rejecting British constitutional monarchy, America was nevertheless dependent on certain goods that could not be produced or bought in the US,. Specifically, in 1794 the country did not have enough copper to mint its coins. It had to turn to England to buy sheet copper.

There is a certain irony in the new coinage being minted from copper brought from the old, colonizing nation against which the US rebelled. This raises the central question for this section: how, when, why and what does a nation discard after a revolution?

In the case of the copper, to forge a national currency and identity, the country had to mint some of its early copper on sheet copper from the UK. Given the economic and philosophical ties between the countries (see “How Far Should a Revolution Go?” in the Content section)ties, what do we mean by independence?

-

Insights

How successful was the American revolution? It’s worthwhile thinking about how we define “success.” Take a look at the three different views on the revolution, below. In your mind, what were the key reasons for the Revolution, and were they won in the end?

The American Revolution was a mistake (2019).

As a counterpoint, here is an article on the benefits of the American Revolution.

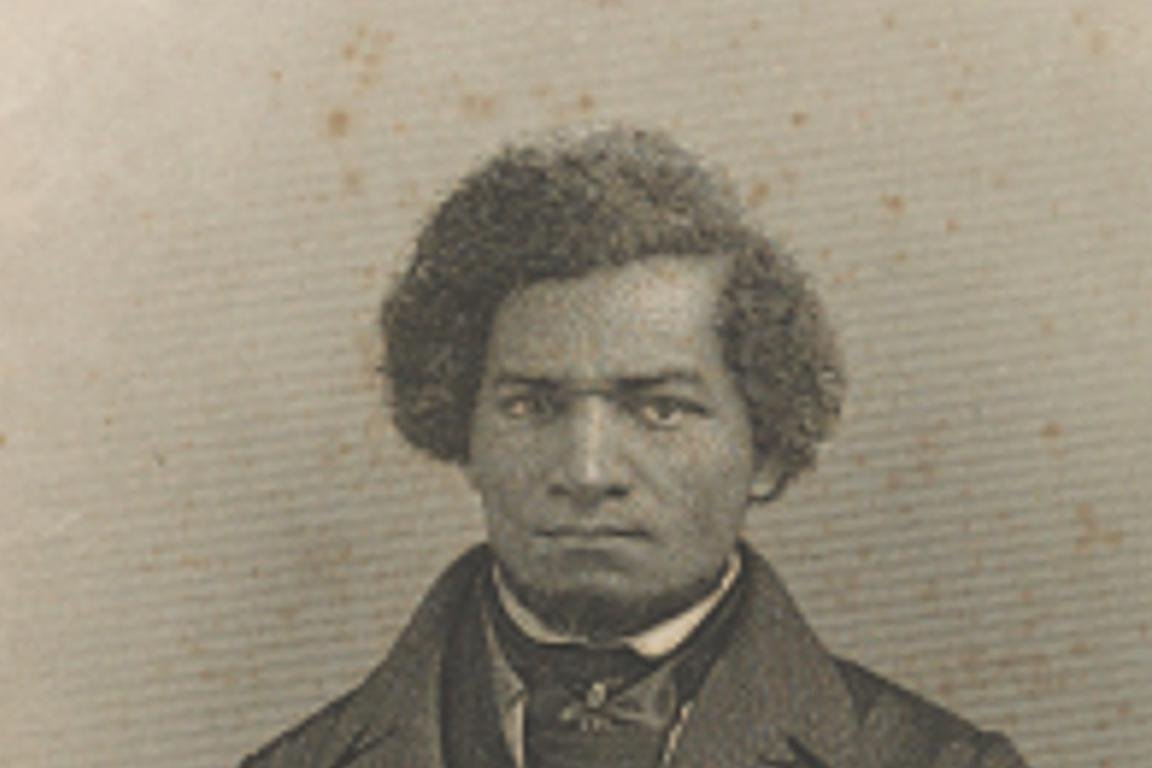

And let’s turn to Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” one of the great speeches about the possibilities and failures of the revolution.

-

Links

Here are a few links that offer further insights into the period immediately following the American Revolution. The final link explores the radical background for the revolution itself.

Video about what happened immediately after the Revolution.

Library of Congress on Creating the United States and the Revolution of the Mind

Questions

Questions help us cultivate curiosity. Use these questions to begin your own journey thinking about the topics. If you’re a teacher, these questions offer you some starting points for class discussion. All questions are designed to encourage people to make links between the topics and their own beliefs.

How much of the colonizing country should a new, post-revolutionary country keep? Why?

Activities

Our suggested activities use cultural artifacts to engage students in thinking through abstract ideas. In other words, we ground the abstract in the concrete. Each learning resource includes a specific focus and objectives. We encourage you to choose relevant materials for your class from the Insights and Links sections above. We hope the Analysis and Links sections provide useful background knowledge for your lesson.

K-6

Goal: Actively think about the power and shortcoming of rules

Outcomes: Younger students will be able to articulate how and why rules work as well as the short-comings of rules. They will practice creating and proposing rules for their classroom or families. Older students will discern and apply principles in situations different from those in which the principles were formed.

Activities: Discussion, listing, writing and illustrating

Time: 30-40 minutes for younger; one class period for older children

Younger: Engage younger students by likening nation to family. Ask students what rules each student’s family enacts. Make a list on the board of these rules. Then ask them what rules they agree with, what rules they disagree with, and what rules they think they should have. This can be as fun or silly as they like. For instance, maybe there’s a rule that ice cream must be served for breakfast. Ask the students what would happen if their rules were kept or broken? The goal here is for students to see that some rules might sound good, but they ultimately might not be good for everyone. As the project for this segment, have students choose a few rules that they think the classroom should enact. Have students illustrate those rules and the consequences of following them. If you want to avoid students creating rules for your classroom, you could ask them to create a new rule for their family that they might suggest to their parent/s. As above, students should write and illustrate the rule, including what the outcome will be.

Older: Ask older children to imagine there is a Mars colony, originally settled by ten countries, including the US. The Mars colonists will know of Earth, but they will never step foot on it. Have students discuss in groups what elements of the US they think people on Mars should know about, and why? Are there any rules or principles from the US that should be part of the Martian colony? If so, which are they? Are there any elements in those rules or principles that they might they decide to change? The goal here is for students to imagine similar questions to those posed before, during, and after the American Revolution, questions about independence and allegiance.

Once students are satisfied with their discussion, add one more twist. Tell them to imagine that the US spent countless trillions to establish the Mars colony. What do the Martian colonists owe to the US and what does the US owe, if anything, to Mars? Have students write a charter for the new Mars colony, from the perspective of the Martian colonists.

7-12 and Beyond

Goal: Explore the paradox of independence and interdependence of countries

Outcomes: Students will be able to locate the sources of objects, find and summarize the politics of that location, and argue for the ethics of using or not using those objects.

Activities: Research, discussion, map making, writing both personal and persuasive, brochure making

Time: Two-three class sessions.

For students at this age, the idea of rebellion is fairly easy to grasp. The K-6 discussions can be tweaked for this age group by asking them what family principles or rules they would eject, and what they would keep or modify. From there, ask them to analogize family to nation. The goal of this section is to help students see the distinction between specific grievances and sound principles. For instance, maybe everyone in the family agrees that fairness is a key rule, but what differs might be the definition or application of fairness.

From that basis of thinking through what would be kept, jettisoned, or modified, ask students to choose one physical object and create a digital map of connection for where and how that object was or is manufactured and sold. There should be time here for students to research their object, including the elements included in the object. Perhaps steer them away from very complicated objects, such as cell phones—or maybe choose one very complicated object to study as a class. For instance, if the class chose a cell phone, or a “world car,” then different teams of students could explore certain elements of the object. Students should list the elements and the sources of the elements. Once the list is complete, ask the students to examine the source countries and how those countries’ values align with espoused national values.

Students will now have a concrete understanding of allegiance to principles and of the sources of the elements in their objects. Ask students to write individually for ten minutes on the following question: In a digital world, how much independence do you think one country can and should have from another?

Finally, ask students to choose an element in their object that is sourced from a country with very different principles from those the student believes in. Depending on their answer to the question above about independence, have students write a brochure outlining a new national policy governing that key element and/or object. The goal will be to clearly outline the issues, and to try to persuade people to their point of view about whether or not we should use elements from countries with whom we fundamentally differ.

If we think of a revolution as an overturning of one set of ideas and the replacement of those ideas with new ideals, if you were alive in 1775, what ideas would you want to replace? And what ideas would you actively promote?

Which approach to revolution do you prefer—the French or the American, and why?