Creating Liberty

Focus: History, Art

Why is Liberty female, and did her gender affect how people thought about Liberty?

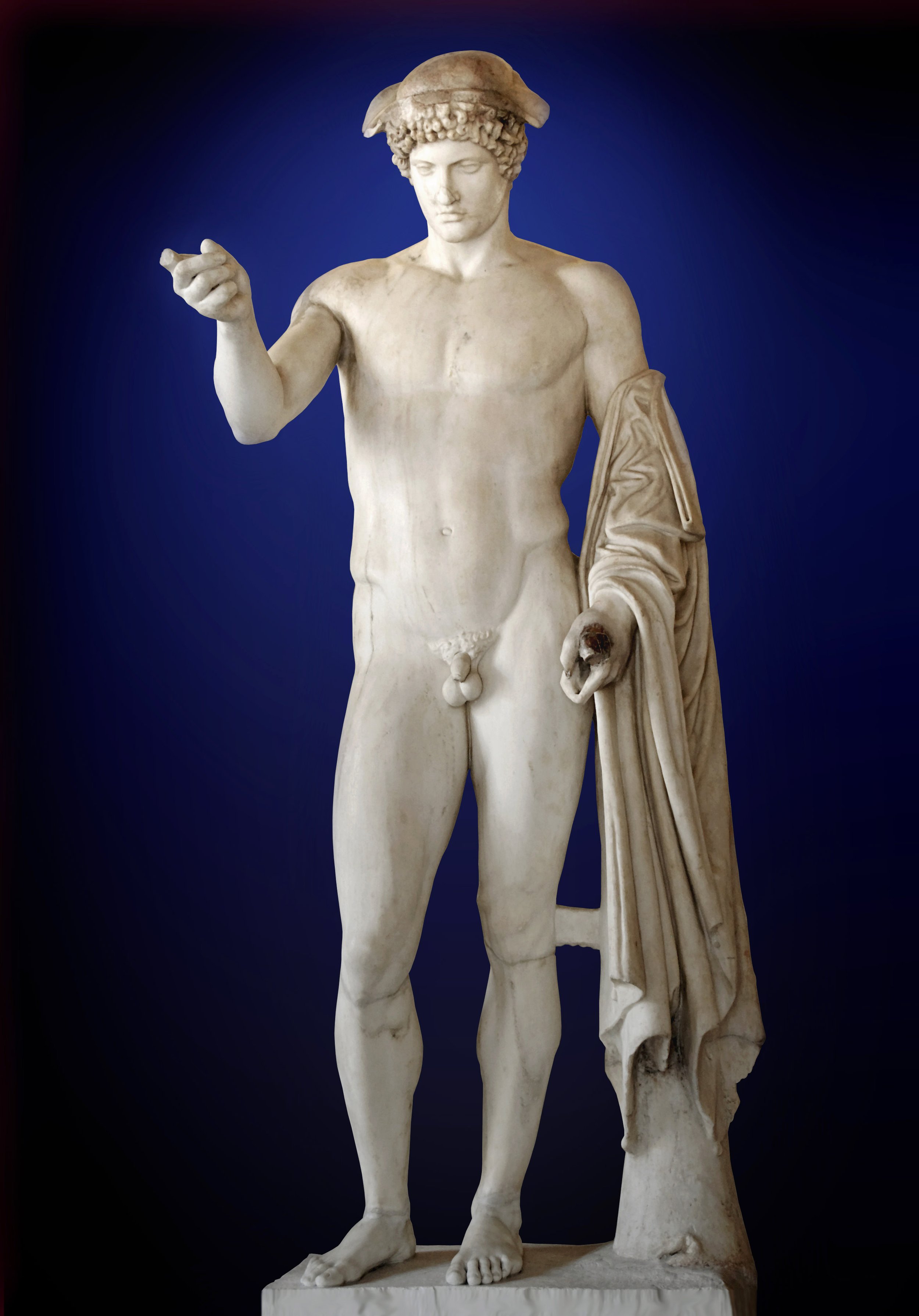

In worlds where there was high illiteracy and beliefs in multiple gods, ideals, values, concepts were translated into sculpture. What made those sculptures recognizable were certain elements that were almost always paired with the god or ideal. For instance, Hermes the Greek messenger usually has wings on his feet, to suggest that he is a god and to suggest speed. This detail allows him to be recognized regardless of what his face looks like. In the picture to the right, the statue has no wings on his feet but has wings on his helmet. There’s a variation, but it’s clear that the sculpture depicts Hermes. The goal of the personification of these gods is immediate recognition, and with that recognition, an unfurling of ideas connected to the god or concept.

Britannia and Liberty

Historically, many of the anglo colonists would be familiar with Liberty. She was often portrayed under the guise of Britannia, the personification of Britain. Indeed, British political philosopher John Locke helped frame the concept of liberty most familiar to the colonists. How do the colonists reject this very British context for their key principle? How do they reframe liberty as distinctively American?

We have a few issues here: the separation of the quality of liberty from the country against which the colonists revolt, as well as the history of the feminization of both liberty and Britannia.

If we stay with the question of Liberty’s power and her gender, it’s worth noting that when the Romans conquered a province, they would allegorize the province with feminine names and qualities. Peter Johnson describes a “relief[s] [in which] Claudius is seen overpowering a semi-naked Britannia who wears a Phrygian hat. Originally worn by a manumitted slave to denote their free status the Phrygian hat or cap later became a symbol of liberty.” Clearly, the goal here is subjugation of the allegorized Britain, and while I cannot see the Phygian cap (what Americans will come to call the liberty cap), her gender, her semi-nakedness, her struggle make her the vanquished. That the Romans allegorized captured provinces as women speaks to the gendered power dynamic.

While Britannia might be subjugated in the 1st century CE, by the 18th c. she has risen as a powerful symbol . No longer subjugated, she leads the country towards a British view of liberty. Her early history of being linked to liberty—if a liberty manumitted by a more powerful force (Rome)—now becomes positive, and she is recuperated as a national emblem.

For the pro-revolution colonists, the separation of Britannia as an exclusive principle of liberty connects with various ways of representing America, such as the “Indian Princess,” the “plumed goddess,” “Liberty” and “Columbia.” Liberty as a fighting principle animates the women of the colonies as it did the men. To the right the first image comes from 1775. Note the scale of allegory, and look at America as “Indian Princess” at the feet of Britannia. The bottom image was engraved by a frenchman after the victory at Saratoga in 1778, when France decided to back the colonies: “America, represented by the Indian princess, kneels at the feet of Liberty. Benjamin Franklin, in Roman costume, is protected by Minerva with her spear and shield. On the left, Agriculture and Commerce look on while Mars, with the Gallic cock (representing France) on his helmet, drives Britain (the naval power) and Neptune back into the sea.”

For all of these allegories, however, during the American Revolution, women fought as soliders sometimes even receiving pensions from the government for their service, as detailed in the link. They were active participants in the fight for liberty for all. Thus, the practical view of women during the active years of the war, 1775-1781 now shifts. As Britannia fought against the Romans, so colonial women fought against the British, but unlike Britannia against the Romans, the Americans emerge triumphant. Liberty wins, aided by women.

It’s worth noting the sad echoes between the Revolutionary War and WW2. During both wars women who worked and fought believed that the different roles they took on would lead to different roles after the war. The women of the revolutionary war faced the same disappointment as women experienced in WW2. Liberty, it seems, extended only so far, and not to all.